A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF NONVIOLENCE: MAHATMA GANDHI AND THOMAS MERTON -A Spirituality of Nonviolence

This thought-provoking article explores the convergence of two profound spiritual thinkers—Mahatma Gandhi and Thomas Merton—on the principle of nonviolence. While Gandhi rooted his philosophy in ahimsa and active resistance, Merton approached nonviolence as a contemplative response grounded in Christian love, peace, and inner transformation. By comparing their lives, writings, and spiritual foundations, this article highlights how both leaders offered a prophetic challenge to the violence and injustice of their times. Readers are invited to reflect on how nonviolence remains a vital and transformative force for personal integrity, social justice, and global peace.

Rev. Binu Rathappillil

7/26/202520 min read

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF NONVIOLENCE: MAHATMA GANDHI AND THOMAS MERTON

This paper undertakes a comparative analysis of the philosophies and spiritualities of nonviolence championed by Mahatma Gandhi and Thomas Merton. While both figures lived in different contexts and drew inspiration from various religious and philosophical traditions, their commitment to nonviolence becomes a transformative force in personal and social domains. Nonviolence practiced and promulgated by Mahatma Gandhi, and Merton forms a common ground and solution for a conflicting world. This research paper outlines unique shades in Gandhi's and Merton's interpretations of nonviolence. This study will shed light on the distinct contributions each made to the discourse on peaceful resistance and social change in the 20th century.

The first part of this research paper explores the life and philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, one of the most influential figures in the 20th century, and his enduring legacy of nonviolence. Gandhi's commitment to nonviolent resistance, known as "ahimsa," played a central role in India's struggle for independence and has left a lasting impact on campaigns for civil rights and social justice worldwide. I will examine the historical context, theoretical foundations, practical applications, and the contemporary relevance of Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence. The second part of the research paper investigates the life, writings, and philosophy of Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk, theologian, and mystic, with a specific focus on his contributions to the discourse on nonviolence. Merton's commitment to peace and justice, rooted in his Christian faith and monastic experiences, led him to explore and advocate for nonviolent resistance during a turbulent period in the 20th century. The paper examines Merton's historical context, the theological foundations of his nonviolent philosophy, practical applications in his writings, and the lasting impact of his ideas on contemporary discussions of spirituality and social activism. The comparative analysis in the final part of this research paper displays the similarities and differences in the philosophies of nonviolence proposed by Mahatma Gandhi and Thomas Merton. While rooted in distinct religious and cultural traditions, both figures shared a profound commitment to the transformative power of nonviolence, contributing unique perspectives to the ongoing discourse on peace and social change. The legacy of Gandhi and Merton continues to inspire individuals and movements seeking nonviolent solutions to the challenges of the modern world.

1. Mahatma Gandhi and Philosophy of Nonviolence

1.1. Historical and Cultural Context of Mahatma Gandhi’s Nonviolence

Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence, shaped by a conjunction of historical, cultural, and personal factors, emerged within the context of India's struggle for independence against British colonial rule. Several key historical factors significantly influenced the development of Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence. India had been under British colonial rule for nearly two centuries, characterized by economic exploitation, cultural suppression, and racial discrimination. The oppressive policies of the British Raj fueled resentment and a desire for independence among Indians. Gandhi was influenced by the Indian spiritual traditions such as Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Gandhi's upbringing in a devout Hindu family exposed him to the teachings of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism, which emphasized the principle of "ahimsa" (nonviolence). The oldest religious writings in history have appeared in India: the Vedas, Brahmanas, the Laws of Manu, and philosophical Upanisads, the two great well-known epics, the Mahabharata, and the Ramayana. The idea of nonviolence was present in all these prayers, philosophical speculations, commandments, poetry, and epics. In the Bhagavad Gita, ahimsa, or nonviolence, is a superior ethical virtue one must attain. From Mahabharata comes the maxim that nonviolence is the most significant religion or duty. These traditions instilled in Gandhi a deep respect for life and a commitment to nonviolence as a moral and spiritual principle.

Gandhi's experience in South Africa was transformative and pivotal in shaping his philosophy of nonviolent resistance. He arrived in South Africa 1893 as a young lawyer to work on a legal case. However, his time there was marked by personal experiences of racial discrimination and prejudice, which profoundly affected him. Before returning to India, Gandhi spent over twenty years in South Africa, where he faced injustice. His experiences there, particularly being ejected from a train despite having a first-class ticket due to his race, catalyzed his activism and hardened his commitment to social justice and nonviolent resistance. Western philosophers and thinkers influenced Gandhi, including Leo Tolstoy and Henry David Thoreau. Tolstoy's writings on nonviolence and Thoreau's essay on civil disobedience profoundly impacted Gandhi's thinking, inspiring his commitment to passive resistance and civil disobedience. Gandhi's emergence as a leader coincided with the rise of Indian nationalism and various movements advocating for independence. He aligned himself with the Indian National Congress and became a key figure in India's struggle for freedom, employing nonviolent methods to challenge British authority.

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in 1919 was a turning point in India's struggle for independence from British rule and had a profound impact on Gandhi's advocacy of nonviolence. On April 13, 1919, during a peaceful gathering at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer ordered British troops to open fire on a crowd of thousands of unarmed civilians, including men, women, and children. British army began shooting into the crowd without warning, wounding over 1650 Indians and killing 379. Gandhi understood for the first time that the British were acting against the Indians in the spirit of terrorism, an expression Gandhi used three times in early April 1919. This tragic event deeply affected Gandhi and intensified his commitment to nonviolent resistance against British rule.

Gandhi's formulation of "Satyagraha," a form of nonviolent resistance based on truth and moral force, was influenced by his experiences and observations of the Indian social and political landscape. He advocated nonviolent protests, boycotts, and civil disobedience as powerful tools for achieving social and political change. Gandhi's philosophy was deeply rooted in Indian cultural values, emphasizing self-reliance, simplicity, and communal harmony. He sought to revive and promote indigenous crafts, promote religious tolerance, and bridge social divisions through his principles of nonviolence and Satyagraha

1.2. Theoretical Foundations for Nonviolence

Gandhi emphasized consistently the need to expose, resist, and transform violence, and he is the most famous proponent of the Twentieth Century's philosophy and practice of nonviolence. Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence was influenced by three vital theoretical foundations that shaped his principles and methods for social and political change. Some key theoretical reinforcements of Gandhi's nonviolence include Ahimsa, and Satyagraha, each of them will be developed below. Gandhi's nonviolence was deeply rooted in spirituality, ethics, and a profound understanding of human nature. His approach to nonviolent resistance inspired movements for civil rights, freedom, and justice worldwide, influencing generations of activists and leaders seeking peaceful social and political change.

1.2.1. Ahimsa

Ahimsa, a doctrine deeply rooted in Indian philosophy and spirituality, exemplifies the practice and principle of nonviolence or non-injury toward all living beings. The term derives from the Sanskrit, where "a" means "not," and "himsa" means "injury" or "harm." Therefore, ahimsa translates to "non-injury" or "nonviolence." Thomas Merton wrote in Gandhi and the One-Eyed Giant:

"In Gandhi's mind, nonviolence was not simply a political tactic which was supremely useful and efficacious in liberating his people from foreign rule, ... on the contrary, the spirit of nonviolence sprang from an inner realization of spiritual unity in himself."

Merton’s words capture what we will define as Ahimsa or nonviolence. For Gandhi, nonviolence wasn't just about achieving political goals, but a way of life deeply rooted in spirituality and moral integrity. He saw it as an expression of the highest form of love and a commitment to truth and justice. He believed practicing nonviolence required inner transformation and a profound spiritual realization of our existence. The Gandhian concept of nonviolence is a principle, whereas Satyagraha is the method of enacting nonviolence. However, Satyagraha is not only a means of achieving unity but is the fruit of inner unity already achieved. The only real liberation is that which liberates both the autocrat and the oppressed, and according to Gandhi, this can be possible only through nonviolence or Ahimsa.

Nonviolence is the fundamental and universal law of our being, a creed that embraces all of life in a consistent and logical network of obligations. A state of nonviolence is part and parcel of our human nature that naturally is held together by peace and unity. Nonviolence does not seek to destroy the evil, the oppressor, or eliminate it by force; instead, it seeks to convert or transform it into good. The ‘vision of evil’ is part of the core of the way to nonviolence. If we see evil as irreversible, then the only recourse is violence and destruction. But evil is seen as reversible; it can be turned into forgiveness, and then nonviolence becomes possible. Nonviolence implies as complete self-purification as is humanly possible. Ahimsa has been integral to various religious and philosophical traditions, including Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. It is considered a fundamental virtue and a guiding principle for leading a life of moral integrity and spiritual growth. The practice of ahimsa extends not only to refraining from physical harm but also to promoting peace, justice, and harmony in all aspects of life.

1.2.2. Satyagraha

The word Satyagraha combines the two Sanskrit words Satya, which means truth, and Graha, which means grasping or forcefulness. Satyagraha is the act of grasping and affirming the truth. Gandhi coined the term Satyagraha, which means "truth force" or "soul force." Satyagraha is a method of nonviolent resistance that relies on the power of truth, moral courage, and nonviolent action to confront and transform injustice. Gandhi's method of Satyagraha provided a way to fight against injustice without relying on violence nor enflaming the forces of hatred and revenge that so often result from armed conflict. At a deeper level, Satyagraha is a means of seeking and testing the truth.

Gandhi emphasized the importance of sacrifice and suffering as essential features of the nonviolent action method. Because of this emphasis on the importance of sacrifice and suffering, Gandhi demanded courage and personal bravery among those who participate in the struggle of Satyagraha, and one must accept suffering to achieve significant changes. Gandhi wrote in Young India, "I have therefore ventured to place the ancient law of self-sacrifice before India. For Satyagraha and its offshoots, noncooperation and civil resistance are nothing but new names for the law of suffering." Nonviolence, in its dynamic condition, means conscious suffering. It does not mean meek submission to the will of the evildoer, but it means putting one's whole soul against the oppressor's will. Gandhi employed Satyagraha as a powerful tool during India's struggle for independence from British rule. His approach involved mass movements, nonviolent protests, strikes, and civil disobedience campaigns, all rooted in the principles of Satyagraha. Satyagraha was a political strategy and a way of life that sought to transform both the oppressor and the oppressed by appealing to their shared humanity and conscience. This philosophy of nonviolent resistance has profoundly impacted various movements for civil rights, social justice, and freedom across the world.

1.3.Practical Applications of Nonviolence

India has a rich history of practical applications of nonviolence in various social, political, and cultural contexts. Some practical applications include the Indian Independence Movement, Salt March and Civil Disobedience, Quit India Movement, etc. Gandhi was the champion, leader, and inspiration for all these movements that led to the independence of India. Directed by Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian independence movement engaged nonviolent resistance as its core strategy. Civil disobedience, boycotts, and peaceful protests were used to challenge British rule, gaining independence in 1947 without resorting to widespread violence.

1.3.1. Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience was a fundamental strategy within Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence, and it served as a powerful tool in India's struggle for independence against British rule. As practiced by Gandhi, civil disobedience was a form of nonviolent resistance. It involved the deliberate refusal to obey specific laws, demands, or commands of the government or authorities deemed unjust or oppressive. Participants in civil disobedience campaigns consciously violated particular laws or regulations they considered unjust. However, they did so non-violently, accepting the legal consequences of their actions to highlight the injustice they were protesting. Gandhi emphasized the moral and political dimensions of civil disobedience. He viewed it as a moral duty to resist unjust laws and to challenge the oppressor's authority while upholding one's own moral integrity. A crucial aspect of civil disobedience in Gandhi's philosophy was the willingness to accept punishment or imprisonment without retaliation. Civil disobedience demonstrated a commitment to nonviolence and the willingness to suffer for the cause. Civil disobedience aimed to awaken the oppressor's conscience, underscoring the moral wrongs within the system, and seeking to bring about change through moral influence rather than force or violence. Gandhi effectively utilized civil disobedience as a strategic tool within the framework of Satyagraha. Movements like the Salt March, the Quit India Movement, and various boycotts and non-cooperation campaigns were symbolic instances where civil disobedience played a central role.

1.3.2. The Salt March

The Salt March was another practical application of nonviolence during India's struggle for independence from British rule. It was a nonviolent protest led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1930 as a powerful act of civil disobedience against the British-imposed salt tax. The primary aim of the Salt March was to challenge the British monopoly on salt production and the imposition of a salt tax, which heavily affected the poorest in India. On March 12, 1930, Gandhi, and a group of seventy-eight volunteers began a march from Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, towards the coastal town of Dandi, which was about 240 miles away. The protest symbolized the disobedience of British laws and colonial oppression. Gandhi walked for over three weeks, inspiring thousands of Indians to join the movement. Upon reaching Dandi on April 6, Gandhi broke the salt laws by picking up natural salt from the shores of the Arabian Sea. This simple act of civil disobedience marked the beginning of a mass civil disobedience movement against the salt tax. The Salt March garnered international attention and support, highlighting the injustice of British policies in India. It showcased the power of nonviolent resistance and became an explanatory juncture in India's struggle for independence. The Salt March demonstrated the efficacy of nonviolent protest in challenging unjust laws and colonial oppression.

1.3.3. Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement, rooted in nonviolent principles and led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1942, was a significant milestone in India's struggle for independence. The Quit India Movement was launched on August 8, 1942, with the primary objective of demanding an end to British colonial rule in India. The slogan "Quit India" became the rallying cry for independence. Mahatma Gandhi played a central role in spearheading the movement. He called for nonviolent mass civil disobedience, urging Indians to adopt non-cooperation with the British government and its institutions. The movement witnessed widespread participation from various sections of Indian society, including students, workers, peasants, and political leaders. People joined protests, strikes, and demonstrations across the country. The British responded to the movement with harsh repression, arresting thousands of leaders, and participants, including Gandhi. The Quit India movement intensified the demand for immediate freedom and garnered international attention to India's fight against colonialism. It demonstrated the unity and determination of the Indian people and ultimately led to discussions and negotiations. Gandhi's leadership and call for nonviolent resistance during the Quit India Movement emphasized the power of mass mobilization and civil disobedience in India's quest for freedom.

1.4.Contemporary Relevance

Gandhi's principles of nonviolence remain relevant and influential in today's world of conflict and war. The words of Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, immediately after Gandhi's sudden exit from this world proved prophetic. He said, "The light is gone, yet it will shine for a thousand years." Martin Luther King Jr., after he visited India in 1959, said, "Gandhi was inevitable. If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, thought, and acted, inspired by the vision of a humanity evolving towards a world of peace and harmony. We may ignore him only at our own risk." Gandhi's influence extends far beyond India; his philosophy and practices have had a profound impact on a global scale. Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolent resistance influenced Martin Luther King Jr. during the American civil rights movement. He adapted Gandhi's principles, employing nonviolent protest strategies in the battle against racial segregation and injustice. Gandhi's principles of nonviolence, truth, and compassion have left an indelible mark on humanity's pursuit of justice, peace, and ethical governance, making him a revered figure whose influence transcends geographical and cultural boundaries. Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence, or Satyagraha, continues to inspire movements for social justice, civil rights, and political change worldwide. His approach of peaceful resistance remains a potent tool for advocating change without violence.

The first part of this research paper explored Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence, tracing its historical roots, theoretical foundations, practical applications, and relevance in global movements for justice and peace. In today's conflicted world, Gandhi's principles of nonviolence offer valuable insights and strategies for addressing conflicts and promoting peace. Gandhi's legacy continues to inspire individuals and movements seeking transformative change through nonviolent means, highlighting the enduring relevance of his philosophy in the 21st century.

2. Thomas Merton and Nonviolence a comprehensive exploration

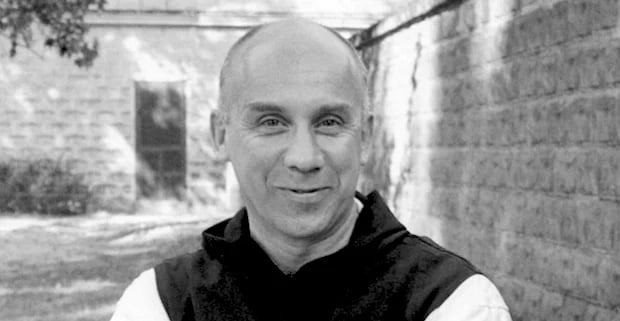

2.1. Historical and Cultural context of Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton, born in 1915, entered the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemane in Kentucky in 1941, where he spent his monastic life. Merton's writings encompass a wide range of topics, with a significant emphasis on contemplation, mysticism, and nonviolence. Merton was born in 1915, amid the World War I. Although he was very young during this conflict, its consequences on the world and its aftermath would have influenced the surroundings in which he grew up. Merton lived through World War II. During this time, he was a student at Columbia University. The war had a profound effect on him and the world, shaping his perspectives and leading him to question the nature of violence and humanity's quest for peace. Merton was a monk at the Abbey of Gethsemane in Kentucky during the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. While not directly involved in the conflict, the tensions and global consequences of this war likely influenced his contemplations on peace, justice, and spirituality. Merton was an outspoken critic of the Vietnam War between 1955 and 1975. He wrote extensively about the moral and ethical implications of war and violence, advocating for peace and nonviolent solutions to global conflicts. His opposition to this war reflected his broader stance against violence and his dedication to peace and social justice.

Merton's spiritual journey as a Trappist monk at the Abbey of Gethsemane provided a foundation for his prophetic voice of nonviolence. His deep contemplative life and experiences of solitude and prayer allowed him to access profound insights into humanity's toiling world and the call for peace rooted in spirituality. Merton's exploration of Eastern spirituality and his significant knowledge of Gandhian principles of nonviolence, particularly his encounters with figures like the Dalai Lama and his interest in Buddhist teachings, widened his understanding of nonviolence beyond Western religious frameworks. This interfaith dialogue expanded his perspectives on peace and nonviolent resistance.

2.2. Seeds of Nonviolence

At the age of fifteen, as a Columbian undergraduate, Thomas Merton took the Oxford Pledge that he would never participate in any war. I admire his bravery and readiness to stand up against war at his younger age. Merton was highly esteemed for Gandhi, especially for how he lived and taught nonviolence. Merton defended Gandhi at Oakham Boarding School in 1930 before his dormitory partners. He cited this experience in his essay "A Tribute to Gandhi" in Seeds of Destruction. "Yet I remember arguing about Gandhi in my school dormitory: chiefly against the football captain, then the head prefect… I insisted Gandhi was right, that India was, with perfect justice, demanding that the British withdraw peacefully and go home, that the millions of people who lived in India had a perfect right to run their country." Merton learned about Mahatma Gandhi's principles of nonviolent resistance and his approach to social change and became deeply inspired by them. Merton's encounter with Gandhi's teachings occurred through reading, studying, and reflecting on Gandhi's works and ideas. He admired Gandhi's commitment to nonviolent action, his emphasis on truth and justice, and his ability to effect significant change through peaceful means. He explored Gandhi's writings as a monk and wrote a book recapitulating Gandhi's philosophy called "Gandhi on Nonviolence." Merton learned about Mahatma Gandhi's principles of nonviolent resistance and his approach to social change and became deeply inspired by them. Merton's encounter with Gandhi's teachings occurred through reading, studying, and reflecting on Gandhi's works and ideas. He admired Gandhi's commitment to nonviolent action, his emphasis on truth and justice, and his ability to effect significant change through peaceful means.

It is fascinating to note that Merton wrote a poem entitled "Fable for a War" in 1939 while studying at Columbia University and won the annual Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer Prize for the best illustration of English lyric verse. Its composition documented that Merton was already deeply sensitive to the catastrophes of war.

2.3. Prophetic Voice Through Writings

Thomas Merton, theologian, mystic, and prolific writer, engaged extensively with the concept of nonviolence in his works. Merton's prophetic vocation was to explore and proclaim nonviolence, deeply rooted in his Christian faith and monastic life, through his essays and poems. He was profoundly engaged in social and political issues of his time, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War era. One of his most notable works on this subject is "Peace in the Post-Christian Era," where he examines the challenges of achieving peace in a world marked by violence, war, and technological advancements. "Raids on the Unspeakable" is a collection of essays published in 1966, and the book explores various social, political, and spiritual issues of the time. Merton explores topics like war, peace, technology, spirituality, and the role of the individual in a complex world.

In New Seeds of Contemplation, Merton reflects on the contemplative life and its implications for nonviolence. He emphasizes the connection between inner peace and social justice, arguing that true nonviolence must emerge from a contemplative and transformed inner life. Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Gandhi on Nonviolence, Faith and Violence: Christian Teaching and Christian Practice, Seeds of Destruction are some of the essential writings where Merton developed his spirituality on the theme of nonviolence.

2.4. Thomas Merton on Christian Nonviolence

"Blessed are the Meek" is an essay in Thomas Merton's book "Faith and Violence". This respective essay focuses on the Beatitudes, a set of teachings by Jesus found in the Bible's Sermon on the Mount. In "Blessed are the Meek," Merton examines the deeper meaning of meekness, a quality often misunderstood as weakness or passivity. He wants to compare this quality of meekness with the principle of Christian nonviolence. According to Merton,

“Nonviolence is perhaps the most exacting of all forms of struggle, not only because it demands, first of all, that one be ready to suffer evil and even face the threat of death without violent retaliation, but because it excludes mere transient self-interest, even political, from its considerations. He who practices nonviolent resistance must commit not to the defense of his interests or even those of a particular group; he must commit himself to the protection of objective truth and right above all man.”

Merton explores how true meekness, as highlighted in the Beatitudes, is a spiritual disposition characterized by humility, gentleness, and a nonviolent attitude. He emphasizes that meekness isn't about being submissive but rather about having inner strength and a peaceful, non-egoistic nature. Merton encourages re-evaluating societal perceptions of strength and power, suggesting that true strength lies in meekness and a humble spirit.

"Christian nonviolence is not built on a presupposed division but on the basic unity of man...for the healing and reconciliation of man with himself, man the person, and man the human family." This unity of man is a significant aspect of Thomas Merton's understanding of Christian nonviolence. He believed that the foundation of Christian nonviolence wasn't rooted in an assumed separation or division among people but rather in humanity's inherent unity and interconnectedness. Merton emphasized the "basic unity of man," acknowledging the shared human condition and the interconnectedness that transcends race, creed, or nationality divisions. Christian nonviolence wasn't just the absence of physical conflict but a proactive commitment to understanding, empathy, and reconciliation. It is derived from recognizing the intrinsic dignity of every individual, irrespective of differences.

By quoting Gandhi, Merton describes a need for a solid metaphysical and religious basis for the constant practice of nonviolence. For Gandhi, this metaphysical basis is the doctrine of Atman, the true Transcendent Self, which alone is absolute, real, and before which the empirical self of the individual must be effaced in the faithful practice of dharma. For the Christian, the basis of nonviolence is the Gospel message of salvation for all men and of the Kingdom of God to which all are summoned.

“Christian nonviolence does not encourage or excuse hatred of a particular class, nation, or social group. It is not merely anti-this or that.” Merton believed that true Christian nonviolence was rooted in love, compassion, and a genuine concern for the well-being of all individuals, regardless of their background or affiliation. It's not merely "anti-this or that," but rather a holistic, positive force grounded in peace and love and a commitment to the well-being of all. This perspective aligns with the broader Christian teachings of forgiveness and the recognition of the intrinsic worth and dignity of every human being.

At the end of his essay "Blessed are the Meek," Merton elaborates seven conditions for proximate truthfulness in the practice of Christian nonviolence. “Nonviolence must be aimed above all at the transformation of the present state of the world, and it must, therefore, be free from all occult, unconscious connivance with an unjust use of power.” Merton was deeply committed to the idea that nonviolence should accelerate transformative changes in the world. For him, nonviolence wasn't just about avoiding physical conflict; it was a powerful force for social, political, and spiritual transformation. Merton believed that nonviolence should actively reshape society's structures, address systemic injustices, and foster a world built on justice, compassion, and understanding. He saw it as a means to challenge and transform the status quo, promoting a more equitable, peaceful, and compassionate world for all.

"The nonviolent resistance of the Christian who belongs to one of the powerful nations and who is himself in some sense a privileged member of world society will have to be clearly not for himself but for others, that is, for the poor and underprivileged." Merton underlined the commitment of those in positions of privilege, particularly individuals from powerful nations, to use their privilege in service of others, especially the marginalized and underprivileged. He believed that nonviolent resistance, practiced by privileged Christians, should be directed towards advocating for and standing in solidarity with the oppressed and disadvantaged. It's about leveraging powerful nations' influence, resources, and position to amplify the voices and address the needs of those often marginalized or silenced within society.

“In the case of nonviolent struggle for peace, the threat of nuclear war abolishes all privileges. Under the bomb, there is not much distinction between rich and poor. In reality, the richest nations are usually the most threatened.” Merton was acutely aware of the existential threat posed by nuclear weapons. He recognized that in the face of such destructive potential, privileged and developed traditional distinctions become nearly insignificant. The threat of nuclear war surpasses borders of wealth and social status, and it endangers all of humanity. He believed that the urgency for peace and the elimination of nuclear threats compelled individuals, regardless of privilege, to work collectively for demilitarization and the prevention of such destructive events.

“The most insidious temptation to be avoided is one which is characteristic of the power structure itself: this fetishism of immediate visible results.” Merton was critical of the emphasis on immediate, visible results, particularly within power structures. He identified an inclination for societies, especially those driven by power dynamics, to prioritize immediate, tangible outcomes. This "fetishism" or obsession with immediate and visible results, in Merton's view, could be insidious because it often leads to short-sighted decisions. He advocated for a more contemplative and thoughtful approach that values processes, inner growth, and long-term sustainable change over quick fixes or superficial outcomes.

"To fight for truth by dishonest, violent, inhuman, or unreasonable means would simply betray the truth one is trying to vindicate. The absolute refusal of evil is a necessary element in the witness of nonviolence." Merton emphasized the integrity of means in pursuing truth and justice. He believed that the methods used to pursue noble causes must align with the values being advocated. In the context of nonviolence, he highlighted the importance of upholding ethical and moral principles even in the face of injustice or oppression.

"A test of our sincerity in the practice of nonviolence is this: Are we willing to learn something from the adversary? If a new truth is made known to us by him or through him, will we accept it? Are we willing to admit that he is not totally inhumane, wrong, unreasonable, cruel, etc.?" Merton challenges individuals committed to nonviolence to examine their openness and willingness to learn, even from those they might consider adversaries or opponents. He raises important questions about sincerity and humility in pursuing truth and justice. His point is about being receptive to understanding different perspectives, even from those with whom one disagrees fundamentally. It calls for empathy, humility, and a willingness to engage in dialogue rather than rigid adherence to one's viewpoint.

“Christian hope and Christian humility are inseparable. The quality of nonviolence is decided largely by the purity of the Christian hope behind it.” Merton noticed a deep connection between Christian hope, humility, and the practice of nonviolence. Christian hope is rooted in the belief that, despite the challenges and injustices in the world, there's a deeper reality of love, justice, and redemption that transcends human limitations.

3. A Comparative Critique of Gandhi's and Merton's Nonviolence

Gandhi and Merton espoused nonviolence as a means of social change and justice; Gandhi's approach was deeply embedded in political activism and direct resistance to colonial rule. In contrast, Merton's approach was more contemplative, emphasizing inner transformation, spiritual growth, and the pursuit of peace within oneself and society.

Gandhi's philosophy of nonviolence, known as Satyagraha, was deeply rooted in his Hindu upbringing. His approach included elements of self-suffering, fasting, and civil disobedience. Gandhi's nonviolence was fundamental to India's struggle for independence from British rule. Merton's insight into nonviolence was shaped by his Christian beliefs as a Trappist monk and incorporated elements of contemplation, inner transformation, and a commitment to social justice. Merton's writings often reflected a broader, global context, addressing issues like nuclear disarmament and civil rights.

Gandhi's philosophy was deeply intertwined with his spiritual beliefs, particularly the Hindu concepts of Ahimsa (non-harming) and Satyagraha (truth-force). His nonviolence was a means of realizing truth and fostering spiritual growth. Merton's nonviolence was grounded in Christian teachings on love, compassion, and justice. His contemplative approach emphasized the need for inner transformation and a deep spiritual connection to inspire nonviolent action.

Gandhi's nonviolence was intricately connected to political movements, especially India's struggle for independence. He believed in active resistance and civil disobedience to confront injustice and achieve political goals. While Merton was engaged in social and political issues, his nonviolence was often expressed through writings, reflections, and advocacy. He didn't participate directly in political movements to the extent that Gandhi did.

Gandhi's philosophy emphasized that the means to achieve a goal must agree with that goal. For him, nonviolence was both the means and the end, reflecting a commitment to moral principles throughout the struggle for justice. Merton similarly believed in the alignment of means and ends, emphasizing the importance of personal and spiritual transformation as a foundation for effective nonviolent action.